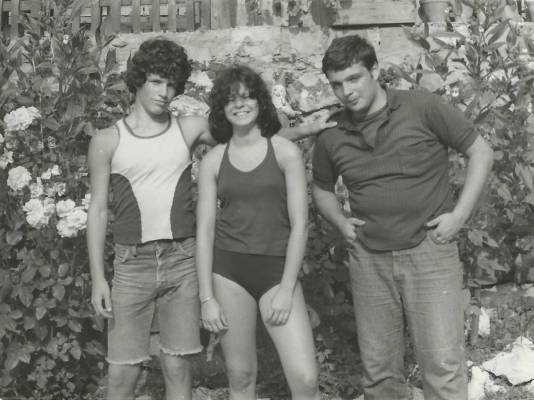

Gender Roles and Feelings

As during the Interwar Period, middle-class norms tended to regulate girls’ conduct much more harshly than that of boys, one of reform education’s most important innovations lay in the area of coeducational instruction and equality of the sexes. At the time, a girl could not be boisterous, engage in mischievous activities, or get her clothes dirty while playing, all behaviours that tended to elicit admiration in a boy. From the beginning, the camp in Bánk took conscious steps toward the emancipation of its female attendees. In Leveleki’s view, the sorts of games played in Bánk – ones that required creativity, spontaneity, and initiative on the part of participants – were boyish in nature. Thus, according to her original pedagogical concept, two-thirds of the population should be boys. An additional expectation was that neither dress, nor conduct should be overtly expressive of gender roles. In the memories of former campers, though this approach felt at first liberating, by the post-1968 period, unisex norms targeting women’s emancipation had lost all real meaning, serving rather to place love and sexuality into the realm of the taboo, while many girls experienced the ban on femininity as limiting, as well. The teenage romances that unfolded from time to time and the difficulties involved in keeping them secret went unnoticed by Leveleki, a person to whom one might turn with any problem, as long as it was unrelated to sexuality and/or emotional attraction – in short, the things that occupied campers’ thoughts the most.

“They didn’t like it if the girls acted too girly, like the kind that pick flowers in the meadow. In Bánk, they didn’t like it if you kept to yourself or only associated with your siblings, because you were supposed to see everyone as your friends – your brothers and sisters. They didn’t like people who were neat freaks or fashion dolls, either (the fashion was for t-shirts anyway). In other words, eminently puritan behaviour was the norm.” (Eszter Bogarász Bánffy)