Elitism

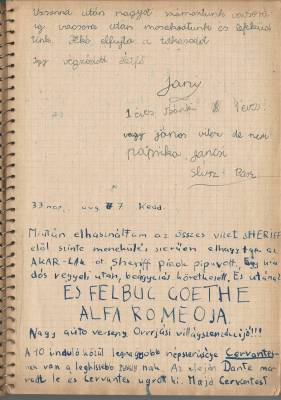

By the 1960s, the popularity of Bánk had grown palpably, its fame spread by word of mouth among the intellectual families of Budapest. Most of the children returned year after year, with new applicants placed on a waiting list or gaining admission through “connections”. In comparison to the average earnings of the time, the camp in Bánk – run on a market model, without state funding – was very expensive and therefore accessible to only a narrow stratum of society. In short, it had become increasingly exclusive. While in the 1950s, children came from families of a variety of occupations, by the late 1960s, most were the progeny of elite intellectuals and artists. It was a circumstance that impacted both the content of games, and the values espoused by the community: to the camp’s original games of wild abandon were added an increasing number that involved intellectuality, creativity, classical ideals, and a measure of the intimacy-irony relationship that comes with them. With the new intellectual content came a certain feeling of exceptionality vis-à-vis “average folk” and “pioneer camp types”. During the initial decades, campers were prohibited from bringing money or expensive toys or clothing with them from home, so that their parent’s social position would not influence their status within the community. By the 1960s, however, this rule had become a privilege of equals: given the high cost of participation – and the social status this implied – there was no longer any significant difference between one camper and the next.