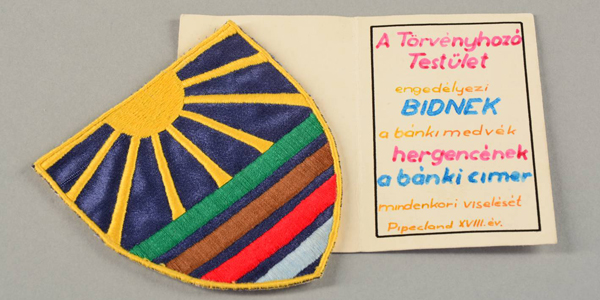

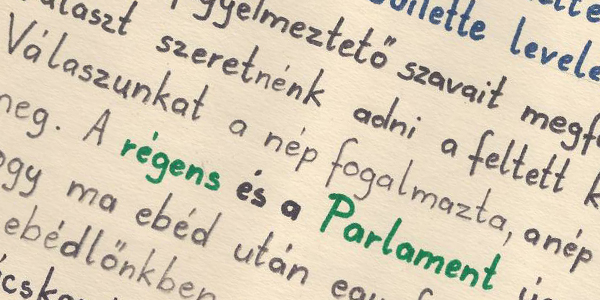

Summer camps in Bánk lasted from early July until the end of August, with children arriving in two groups of about thirty or forty each. Campers ranged from three to fourteen years of age and included both boys (cubs and bears), and girls (witches). Leveleki’s concept required that the boys always be in the majority, a rule that set both the tone, and manner of execution of all-camp games. Surviving descriptions of large-scale role play activities, such as “capture-the-flag battles” with fictive external enemies (pirates, bandits, “fish-tailed blood-suckers”), paint a striking picture of the symbolic universe that reigned within the camp’s borders. Ordinary days were filled with various contests and competitions, including plum-pit spitting, balance beam walking, tabletop football, and tongue-holding. Also key from the standpoint of atmosphere were the camp’s various special days and celebrations: “Anna’s Ball” in late July, the national celebrations on August 20, and the camp’s own special brand of “Olympic Games,” organised every four years in parallel with those of the “outside world”. Some of the songs, games, and programs that arose from these special days are now legendary, having become part of an extraordinarily potent system of traditions that, passed from one generation to the next, have helped maintain the continuity of the community. The camp favoured its own ideal character, embodied by the word klassz, meaning “super” or “cool”. In camp parlance, a klassz kid was one who was original, savvy, daring, creative, and community-spirited. In recognition of this quality, there was the “Bánk Nobel Prize” known as the bear cap, which was accorded on festival days to those Aunt Eszter deemed worthy. A vacation in Bánk consisted not only of various events, but also exactingly constructed ordinary days. The order of daily activities and games created a peculiar sort of world apart, a miniature society known to the children as “Pipecland” [pronounced pee-petz-lahnd]. This children’s state was governed as a constitutional monarchy, with a king, a regent, ministries, and laws, and included its own set of institutions, such as an opera house, national theatre, and internal newspaper – the Bánki Béka Brekegi – edited by the children.

Manifest in everything the campers did were the principles of reform education, which aimed not only to fill up the children’s free time, but to nurture and educate them, as well. Attention was paid to fostering campers’ physical, intellectual, and mental development, while at the same time constructing a community that was creative, active, and true to its own set of standards. The reality of Bánk consisted in an internally created, multigenerational, symbolic world that while coeducational, was constructed over fundamentally masculine norms.

“I always strove to create a community, while at the same time respecting individuality and personal differences. Individuality and independence are both extremely valuable, but the goal of our camp was to create a good community atmosphere.” (Eszter Leveleki)